By Robert Santana MS, RD, SSC & Mark Rippetoe

In my previous article, I noted that perceived difficulty is the most common reason for an artificially weak deadlift. Another common reason is that lifters often repeat or reset loads due to an inability to maintain lumbar extension off of the floor. Meanwhile, the squat continues progressing while the lifter continues repeating and resetting the deadlift for several weeks in a row. This results in a squat that equals or exceeds the deadlift.

A weak low back is an obvious contributor to artificial deadlift weakness. The lack of kinesthetic awareness of the low back is a common reason for this that is easily addressed through a combination of verbal and tactile cueing. Inexperience with pulling a load from a completely stationary position off the floor often results in lumbar flexion upon initiation of the pull. Since the role of the low back has been beaten to death in various other articles, videos, and websites, I won’t spend much time on it here. Instead, a discussion of the arms and various power leaks that present between the shoulder and the fingers is something you may not have considered. Properly setting the arms, wrists, and hands into position will contribute to maintaining spinal extension during the initial pull off of the floor.

The Hands

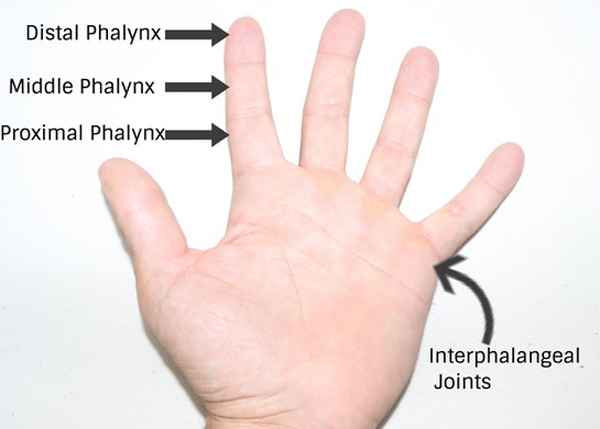

It amazes me how often the hands are overlooked when assessing pulls from the floor. The hands are the direct point of contact between the lifter and the barbell. It is clear and obvious that a secure grip is essential to move the bar from the floor to the lockout position. A correct grip results in the bar being placed on the proximal phalanges somewhere between the middle and proximal interphalangeal creases.

This is just below the interphalangeal joints (i.e. the region at the finger-side of the palm of your hand where your calluses form). I have seen many lifters at all levels of advancement attempt to hold the bar in the center of the palm. This results in the bar sliding down the hands into the fingers upon the initiation of the pull. This is often accompanied by flexion of the phalanges, metacarpals, and wrists, all of which combine to produce a downward change in the position of the bar in the grip if the weight is heavy enough, resulting in a power leak.

Slack in the hands leads to a loss of spinal extension during the initial pull off the floor. This probably occurs due to the back sensing the loss of tightness at the beginning of the kinetic chain. The kinetic chain begins with the hands, followed by the wrists, forearms, elbows, upper arms, shoulders, trapezius, and eventually the thoracic and lumbar erectors, in line before the hips and knees which actually generate the force of the pull. It is well known that the back will not pull what the hands cannot hold on to – this is probably a safety “feedback loop” that prevents injury.So if gravity pulls the bar down out of the grip, the thoracic and lumbar spine tends to follow the loss of power transfer. In essence, a “domino effect” down the kinetic chain starts with the barbell sliding down in the hands and ends with flexion of the spinal erectors.

The Wrists

The wrists are the next anatomical structure up the chain. Wrist extension often accompanies soft fingers. This is often an artifact of the lifter leaning on the bar, essentially resting in compression on the bar prior to the pull. This could stem from listening to coaching instructions during the first deadlift session, or from the lifter attempting to preserve contact with the palm and the barbell as in the squat, bench press, or press. Pulling from this position results in the wrists falling into a neutral position, the grip not starting the pull tight, the bar sliding down the hands, the spine losing extension, and possibly torn calluses. For the coach, a useful tactile cue is to pull up on the trainee’s arm and forearm until the wrists, hands and fingers are fully stretched. Be sure to instruct the lifter to maintain his grip on the bar while you do this, otherwise he will release the bar as soon as you apply pressure. The verbal cue would be “Pull the slack out of your wrists and arms.”

The Elbows

Bent elbows on a deadlift are fairly easy to identify and correct. It is common for many lifters to set up with bent elbows. This often occurs because the lifter is either resting on the bar, or attempting to retract the scapulas because he was told to do so in a social media post, not paying any attention to his elbows. Emphasizing Step 4 along with the tactile cue described above often corrects this issue quickly. Another reason this occurs is because the lifter “shoves the knees out” in Step 3 excessively, resulting in the knees unlocking the elbows. The correction for this is to instruct the lifter to straighten out the arms and to merely “touch the arms” with the knees. This is one of those examples of an obvious and easy fix through reminders and tactile cueing.

The Shoulders

The shoulders represent the proximal end of the arm-wrist-hand system and the most commonly addressed. Step 4 on the 5-step instruction addresses the shoulders when the lifter is instructed to “lift the chest.” This is not the same thing as “shrugging” or retracting the shoulder blades, which should not occur – the traps and rhomboids are used isometrically in a deadlift, not in concentric contraction. By lifting the chest, the shoulders are pulled up away from the floor, which results in an extended thoracic spine. This should also pull up on the arms, elbows, wrists, and hands if done properly. However, this is often done incorrectly and oftentimes the lifter raises the chest but fails to lock out the remaining structures of the arms. If this occurs, be sure to check your lifter’s hands, fingers, elbows and shoulders and make sure they are fully extended while keeping the chest up.

And any pull that starts with slop in the fingers, hands, wrists, elbows, and shoulders is a pull started from the chest artificially close to the bar, with the back angle too horizontal in an inefficient position that increases the ROM of the pull unnecessarily. A deadlift should use the shortest ROM possible, so more weight can be lifted, and this is why we pull with the closest grip outside the legs we can manage. Don’t undo this advantage by failing to pull with the “longest” arms you can manage.

The Breath

The timing of breathing is a “non-arm” power leak. We all know that we need to hold our breath during all lifts. However, it has been my experience that nearly all novices hate holding their breath on deadlifts. The breath is often taken as an involuntary cue to start pulling the bar off of the floor (i.e. “grip-and-rip”). Painful as it may be, the setup of the deadlift should take place with a held breath. One way to do this is to breathe before bending over to take the grip. A more common and easier method is to avoid setting up until the inhalation is completed. For those with belly fat, it may help to roll the bar away to stretch the torso out in the bent-over position, thus allowing for a deeper inhalation, followed by rolling the bar back in to the mid-foot position for the start of the deadlift. This is commonly performed in strongman competitions, but is not recommended for novice lifters since it usually results in the bar being pulled with hips too low and the bar forward of the mid-foot.

Once the breath is held, lift the chest, fully extend the arms, wrists, and hands, hold this for 1 second, then begin pulling. That 1-second hold will likely be perceived as 5 seconds, and is the most important step in the setup, because it gives you time to make sure the low back is in extension before your pull. In other words, you must perform an isometric pull against the bar in the correct pulling position before the actual deadlift. The perception of an eternal static hold is normal, and you may get dizzy the first few times you do this. Eventually it becomes normal and you won’t pull any other way.

The deadlift is technically the simplest lift we perform, but also one of the easiest to make mistakes on. As a result, many lifters get stuck constantly repeating and resetting loads due to an inability to maintain an extended lumbar spine. The most common errors related to initial low-back flexion are often the result of power leaks in the arms and improper breathing. By fully extending the fingers, hands, wrists, and arms, the spine will more easily maintain an extended lumbar position. Holding the breath and performing an isometric pull prior to the dynamic will complete the setup process. The result is more weight on the bar and thus a stronger back and improved aesthetic appearance of the upper body. So next time you deadlift, hold your breath, stretch your arms, and “pull before you pull.”